It is a pantheon of concrete and steel.

It is a city that rises defiantly in the delta alongside the father of waters.

It is the humidity of autumn evenings that drapes stately oaks and broad magnolias.

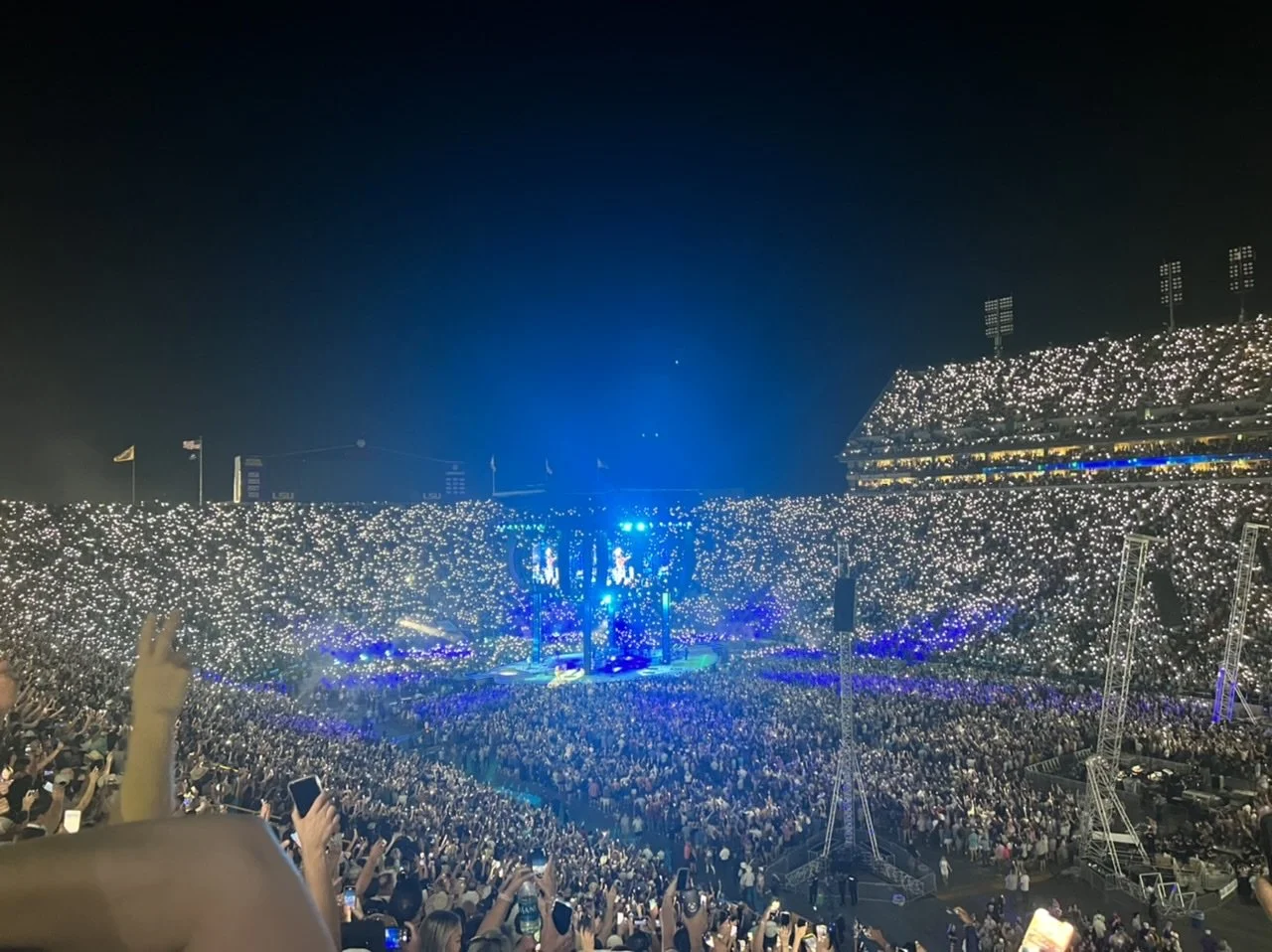

It is haunted ... and it is loud.

It is Halloween night and Cannon blasts.

It is a Louisiana gumbo of humanity that cheers its Tigers to victory and destroys the dreams of invading foes.

Chance of rain is ... never!

It is the cathedral of college football and worship happens here.

When the sun finds its home in the western sky, it is a field of glory for sure...

But much more than that, it is a sacred place.

And it is Saturday night in Death Valley.

—“Saturday in Death Valley” by Dan Borne

I grew up a Tiger.

Nevermind the handful of pictures of toddler me in A&M shirts or sweatshirts; I was born in Bryan, Texas — practically in the shadow of Kyle Field — and I don’t remember wearing them, anyway. I have no memory in my life of a time before purple and gold, nor of spelling “go” without a few extra vowels.

I grew up attending games, but my first year as a student brought me the 2003 season, and the UGA game in particular. I got chills just from typing that, as I do every time I think about the crowd spontaneously bursting into the L-S-U chant after the Bulldogs tied it up late. The crowd willed victory into existence. Skyler Green’s ensuing catch was preordained.

Then followed a slew of great memories of LSU football’s modern glory years:

Paying witness to the defiant will of Louisiana and her inhabitants during the hurricane-marred 2005 season.

Then graduation, hopping onto the 2007 roller coaster season and carousing through the French Quarter to celebrate a home-brewed championship.

2011’s greatest regular season of all time. (And thanks again to the Quarter, precious few memories from that year’s championship game.)

In 2010, the girl I brought to the Alabama game took a tailgating-assisted tumble on the sidewalk. Scraped up and offhandedly complaining about a sore shoulder, she was still a trouper and made it through the game. Two weeks later she had to have surgery for a grade-two dislocation. (I sent flowers.)

I’m still grateful for her toughness, because since then I sat through the consecutive crimson heartbreaks in 2012 and 2014, and the consecutive shutouts in our last two home contests.

That bitter taste has been bolstered by the bold seasonings of sleepwalking through a shutout to basement-dwelling hogs, last-second bowl losses, and the ignominious ends to our winning streaks over Miss State and the Aggies.

But it’s the bitter that makes the sweet, and we still win more than we lose. There’s no team in this country — nor any fan who attends — who leaves a Saturday night in Death Valley the same.

So... I get it. I know what makes Louisiana, and LSU in particular, special. I’m a fan not just by upbringing, geography or pedigree. I’ve lived it.

I’ve paid my Tiger taxes: Making the long drive across I-20 and down I-49 for games, and buying tickets, parking passes, and the new branded Nike Free shoes (which are, by the way, the most comfortable I own and worth every penny).

But those things aren’t what true fandom is about.

I’ve spent many years reveling in worship in the cathedral of college football, but I admit my rites and rituals were empty. I’d never claim to actually bear the purple and gold stigmata.

My indifference was justified by practicality, equivocation: It’s a business. It’s a fun hobby but only a game. They’re just kids trying to get a degree or make their living.

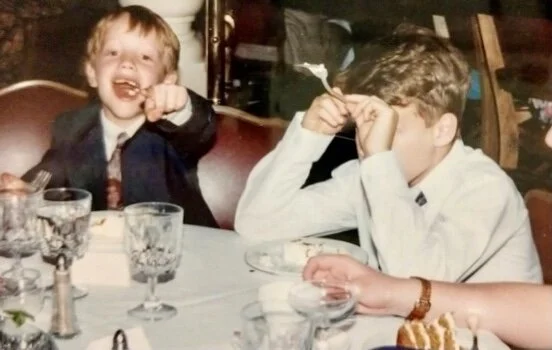

And then suddenly last year, my father and my little brother — fans, true fans — were gone within four months of each other. The former unexpectedly, from a cardiac event; the latter after a rapid but agonizing battle with cancer.

Yet neither were officially alumni: My dad left LSU a semester shy of graduation, and my brother was an ABC after graduating from Rhodes College in Memphis. How true a fan can you be without the necessary paperwork? Purely, it turns out.

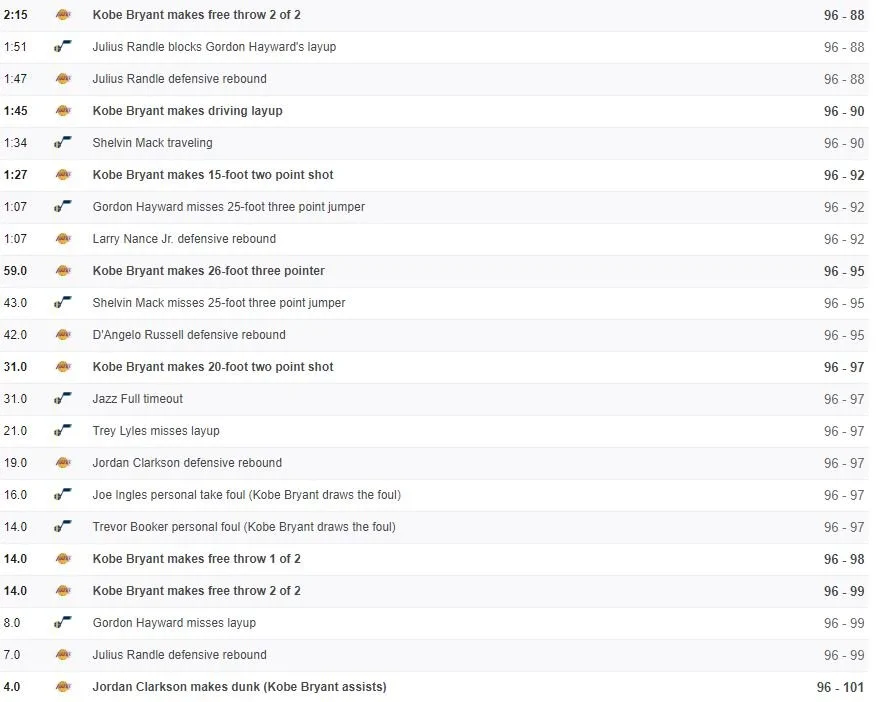

My dad: In 2013, he suffered symptoms we feared might be a stroke. As a type 1 diabetic, he had a number of health problems, and our family was familiar with both of Fort Worth’s main hospitals. We asked him which one he wanted to go to. His answer: "The one with ESPNU." The game (UAB) would be on the next day.

As he was checked into the ER, the triage nurse asked him standard assessment questions, including if he'd ever thought of harming himself or others. His slurred response: "Do you know who Nick Saban is?"

My brother: He was an Aggie-leaning youth, but we really won him over as a teenaged guest to the student section at its best, amid one of those frenetic moments — the snarl of a tiger, cornered, ears back, vicious, continuous — when he turned to me with his eyes wide and mouth open, unable to hear his own screams. And later, as a former high school defensive backs coach who appreciated good defense.

On his deathbed in October, four days before he’d be gone, and the day after the Miss St game — after a family friend got word to Coach Aranda that a guy to whom he’d already sent an encouraging note was in his final days, and Aranda replied that they’d “dial one up,” then throttled Moo U — my little brother pointed at the door and said he wanted to go to Tiger Stadium.

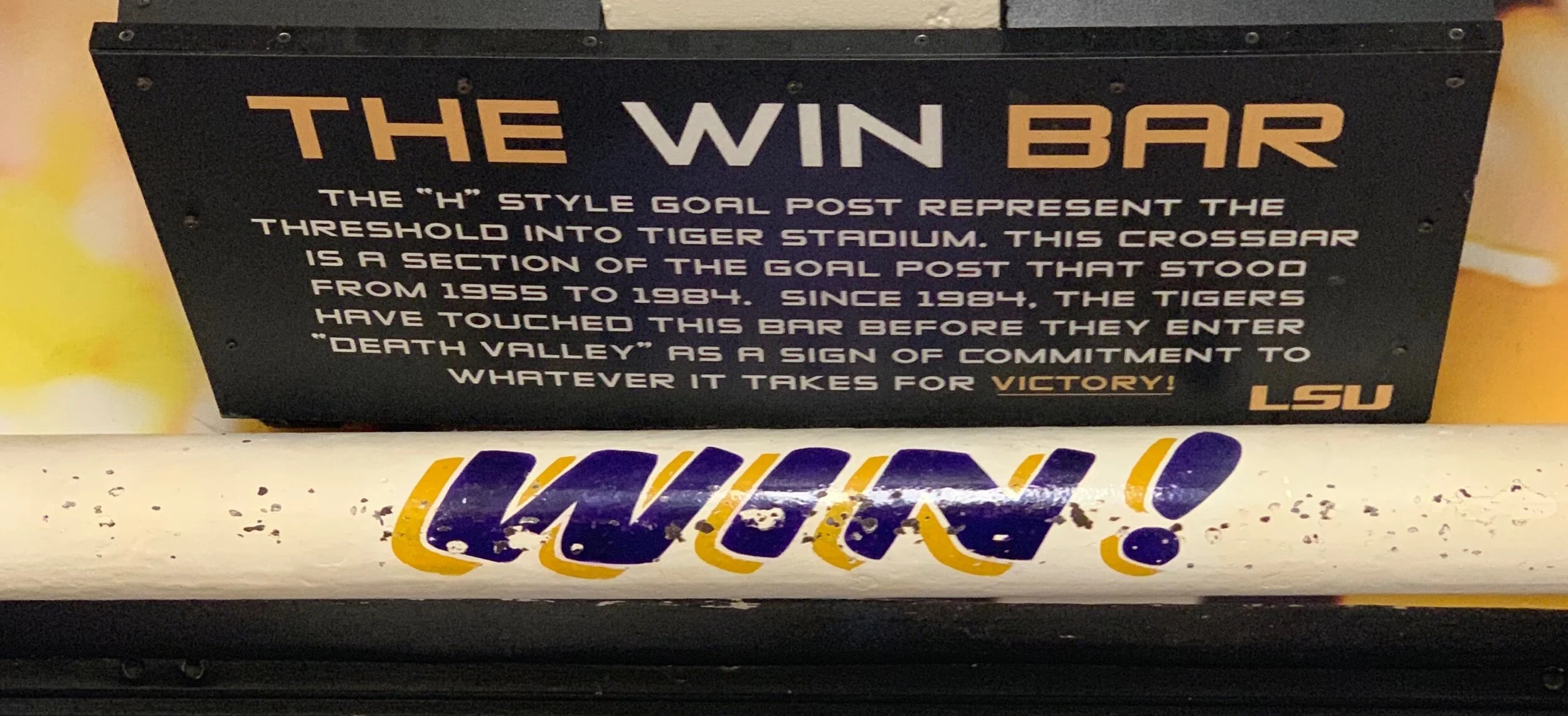

No framed sheepskin of mine outweighs the credentials of men who saw death waiting on the other side of the chute and touched the Win Bar on their way out to meet it.

The diseases that killed them weren’t infectious, but the Tigers are: Now my Aggie mother and Badger sister-in-law say they’re our fans, too.

In September, I cried in Jerryworld because my dad missed the Tigers’ playful romp over Miami. I shed tears writing this thinking about the last text my brother would ever send me, amid the riotous celebration following the unexpected delight of beating down previously unbeaten UGA in October: “Looks like crunkville down there.”

I tear up thinking not just about how much I miss them, but how much they will miss: More heartbreaks, assuredly, but also more championships.

They’ll miss our post-game debriefs at my uncle’s table, around cold Jay’s BBQ sandwiches or steaming bowls of crawfish stew. They’ll miss cursing at Gary Danielson’s haughty insolence and the interminable length of CBS commercial breaks. They’ll miss the inevitable ecstasy of throwing off the crimson yoke.