My grieving process began in 2016 — March 5, to be specific, the day my grandmother passed. Her protracted decline offered a front-row seat to the heartbreak of my chronically ill father, undoubtedly also grappling with his own mortality in his own stoic way.

I drove him down to Baton Rouge to visit her, near the end. It had been several years since I’d been close to someone who only had a foot left in the door of life. In that familiar living room turned hospice ward, I felt for the first time the chest-crushing grasp of anxiety that would be become a close companion in coming years.

I ignored it, as I had any emotional vulnerability for years. I cried during her funeral service, an ocular contact allergy to funeral services I still possess. The heavy weight of loss was leavened by the Hebraic tendency toward levity.

So I moved on. Her decline was so protracted and her stubbornness of life so intractable, it felt like she had evaporated away slowly instead of being here and then gone suddenly. A lioness was gently pet to sleep by devoted nurses and doting children.

Which naturally brings me to Kobe Bryant.

About a month later, he was going to play his final game: the 16-65 Lakers vs. the 40-41 Jazz. The all-time great deserved to go out more honorably than hobbling through a tanking season, but we don’t get to author our own screenplays; we just write the dialogue.

I sat down to watch this little digestif of history, expecting little more than a curtain call for a staple of my youth and formative adulthood. He was the Xennial NBA star, sandwiched between Jordan and LeBron. I had even been treated — an odd word for a Houston fan — to seeing him hitting a dagger three against the Rockets in the momentous 2009 season.

It felt inevitable: The Rockets took a single-point lead with under a minute to play, but Kobe buried a 27-foot three with 27 seconds left, and that was it. We all felt it coming; he simply felt it; and that inimitable shot and swagger was impressive to witness in person.

The Lakers and Rockets would go on to a six-round heavyweight fight for the de-facto championship in the conference semifinals that year. The Lakers won, of course, then claimed the penultimate championship of the Kobe era.

Fast forward several years, and the tyranny of aging and the cyclical nature of NBA rosters had reduced the Lakers to a rump state and Kobe to a Wizards-era Jordan: A legend you dare not besmirch, but not because the Mamba still had venom.

But I watched. I admired his commitment to a single franchise, to retire wearing a single uniform whose colors I admittedly don’t mind. I have a distinct memory of watching a late-era Jordan take a game-winning shot and missing it. Would Kobe follow the same quiet end, or was there one more 27-footer in him?

So I watched.

The Lakers were losing, unsurprisingly, but Kobe was scoring buckets, with more than 30 points through three quarters. Down 12 with under 10 minutes to play, he hit a three. Under 10 points is doable. The Jazz responded with a three. Kobe hit another one. The Mamba flicked his tongue, tasting victory.

And I watched.

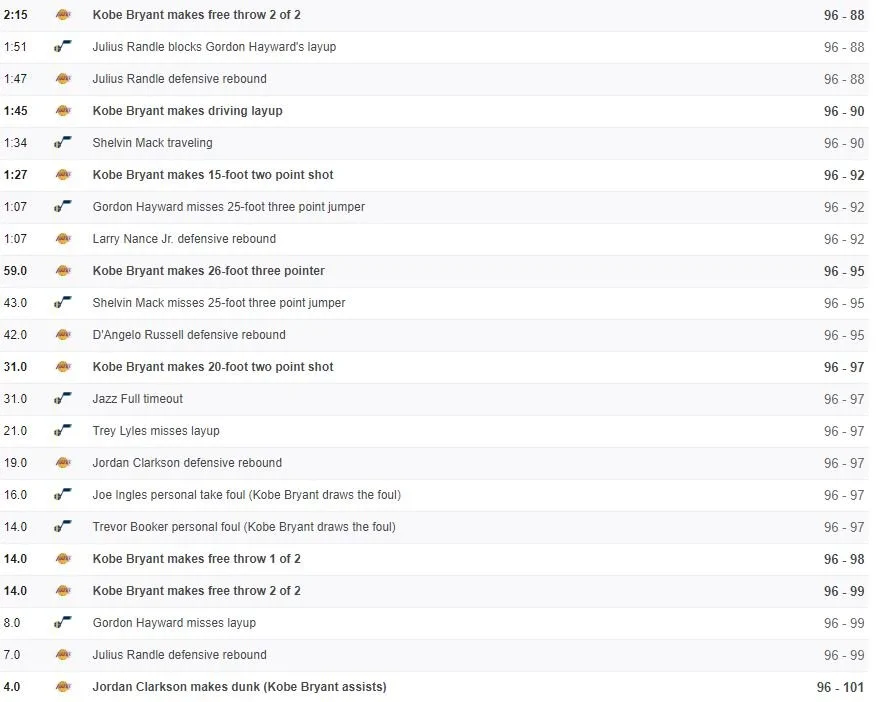

Down 10 with just over three minutes left, Kobe Bryant scored 17 straight points for his team, dished an assist for the icing dunk and a 101-96 lead with four seconds left, and left the court a winner.

Most of the talk about that game centers on his 60-point performance, but that’s not what impresses me; it was the way he emptied his tank in the last quarter of his playing career. He didn’t score points to look good. Kobe abjectly refused to end on anything but a win.

I wept for a player I’d never possessed any specific affinity for, on a team I didn’t care about. Maybe because it was so esoteric, a titanic performance for a mere 17th win on the season. Maybe it’s because I knew these events were somehow connected, somehow.

Part of me recognized I was witnessing an end, albeit of a different kind, and my refusal to process the grief of losing my grandmother was manifesting itself in tears for a basketball player.

Which naturally brings me to my dad.

My dad had a saying: End on a make. I’m sure all of his players learned that during his coaching days, but it was just as true shooting hoops in the driveway as a child. You don’t walk off the court (or concrete) without your last shot going through the hoop.

Maybe it’s nostalgia. Maybe it took losing all of these people to recognize the temporal nature of greatness, in all its forms: Player. Coach. Parent. I cried again yesterday, but not because I was sad a basketball player had died. I cried for the grieving, with sympathy for the pain of sudden loss. I cried for the loss of idyllic childhood moments.

I mourned the loss of greatness.