Before the past couple of years, I could probably count on one hand the concerts I’ve attended:

Steve Miller Band at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo in high school, featuring underwear-bearing and panty-throwing middle-aged women

A clenched-jawed, violently hungover 21st birthday gift to a roadhouse to see Randy Rogers

Sister Hazel at Fort Worth’s Main St. Arts Festival

The LA Phil at the Hollywood Bowl, twice — once under the charismatic Bramwell Tovey and once under the venerable John Williams

I’m surely missing some, though surely I’d have no need to incorporate toes for an accurate number. Concert attendance remained an uncommon enough event that most of them stand out, and most were undertaken at a once-every-few-years cadence.

Why? Part of me thinks the vast majority of artists sound better when recording music in a controlled studio environment. Partly it’s the noisy, crowded environment, anathema to an introvert. Partly cause I just didn’t get it – why would you go to a chaotic, live, possibly lower-quality event where everyone is singing or yelling, when you could listen to an album with a good pair of headphones and catch all the nuances in the recording?

Partly it’s the simple fact that I like music, but I am probably in the midpoint or lower of music appreciators. Music will move me emotionally and has been the soundtrack to my life like any normie, but I certainly don’t have the range or depth of interest to separate me from a passionate fan or proper artist.

If anything, my relationship to music has cooled over the past few years. This grief journey, which has led to being emotionally open to new experiences, also coincided with developments like owning newer vehicles that don’t even have a CD deck anymore – gasp! Forced to enter the era of compressed streaming audio, I’ve enjoyed indie radio stations and discovering new music but became more likely to treat music as background noise rather than an album to be experienced.

Which naturally leads me to Albert Camus.

In a recent piece, philosopher Sean Illing explains the dangers of living in a society that elevates abstraction over experience. He references Camus’ post-WWII concerns about hazards inherent to abstractive ideologies and the resultant spiral to political nihilism. Particularly incisive is his observation that nihilism doesn’t necessary refer to believing in nothing, but to refusing to believe in the world as it is. Nihilism is despair. But he also elucidates how braving those hazards can lead to sharing some of the noblest human bonds.

Like Frankl’s logotherapy, Camus posits that there is a certain solace amid horror, be it disease or war or disaster – any horror sufficient to forge necessary community among calamity. Right now, that could mean we share outrage at the plight of Ukraine, or a coursing pandemic, or for Uvalde, but…we share. Being together in that resistance – that defiance – for something better is a collective bond with your fellow citizens, our fellow human beings.

“The problem is that solidarity often slips away in the mechanics of everyday life. But the empathy and love fueling that desire to help in a crisis is a constant possibility.”

And that possibility is a choice we can choose to make every day. Within that choice is the lens we will use to see our world: defiant optimism or ideological pessimism. Or to paraphrase Camus: optimism is to resist despair.

Which naturally brings me to Garth Brooks.

The day before Garth’s literally earth-shaking concert at LSU’s Tiger Stadium, I probably could’ve been convinced to give my tickets to a deserving pair. They were a cherished gift, but hey – it’s just a concert. I don’t really go to concerts.

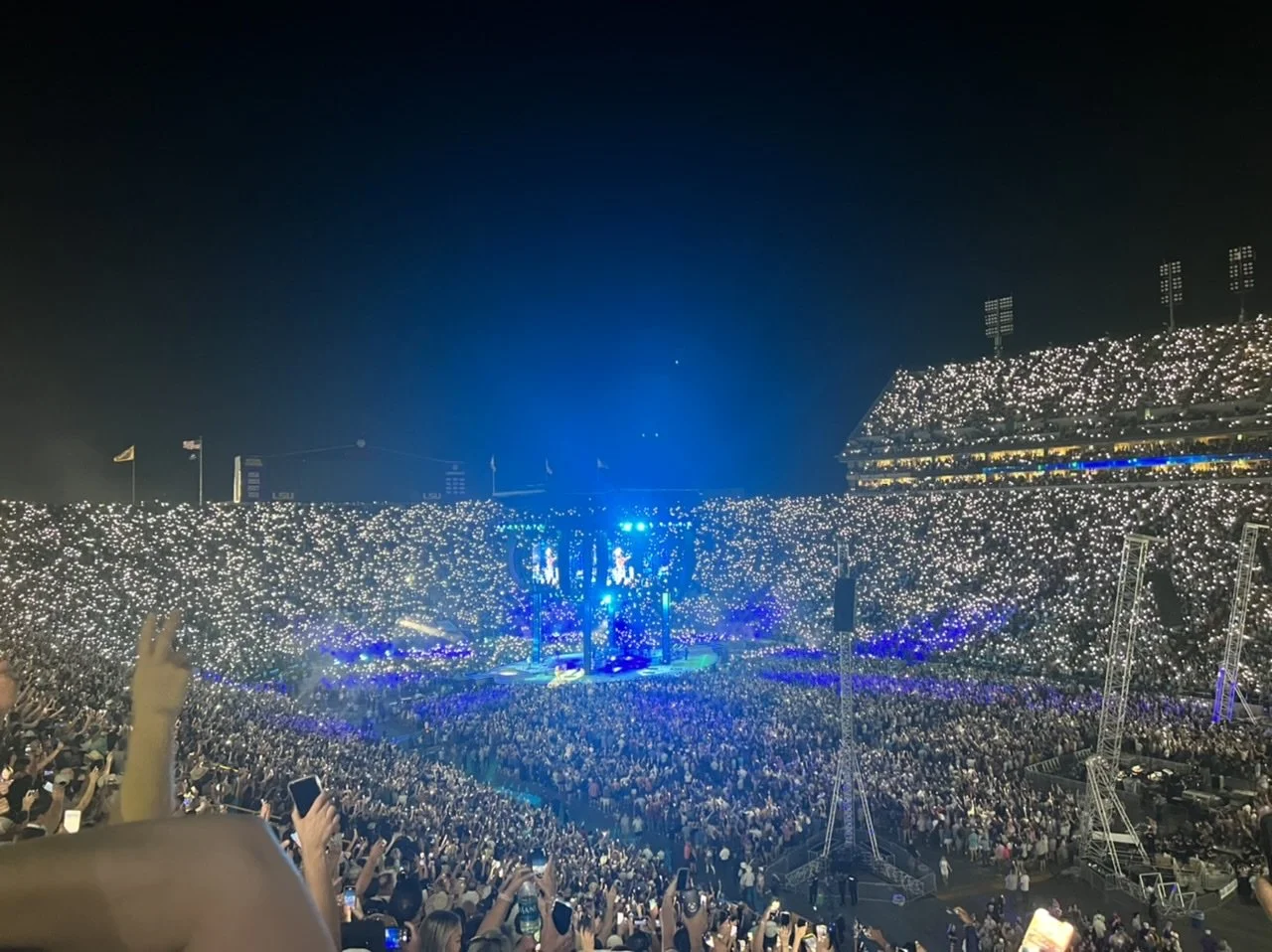

Fortunately, nobody asked, so I went in expecting merely a pleasant experience in a hallowed location. But before Callin’ Baton Rouge tipped the campus seismograph, 102,000 of my colleagues gave me a revelation. As did Garth. Some residue of self-consciousness had obscured it until then, but all those people were there to sing songs with him, and he was there to listen to them sing. The point of the concert was to be there together.

Hello, Samantha dear.

Reflecting on why I was so emotionally moved by a community singalong, it occurred to me that for an admitted word dork, it hadn’t occurred to me before that “community” etymologically refers to together-service: one voice among many, among 102,000, but singing one song.

On the drive home, I stopped to visit Menachim Aveilim, the cemetery in Lafayette where my dad rests. The grass has grown over the gravesite. The dirt is level. It looks like it belongs there, not like a fresh maiming of Earth. It is a scabbed-over wound; the healing is underway. For the first time since his interment, I did not cry when standing above my father’s grave.

I visited during the ongoing Festival International de Louisiane, a music and arts festival. Amid the drizzle of a spring shower and poncho-muffled voices of the gathering celebrants, the sounds of fiddles and gospel choirs drifted through the raindrops.